What Does GOP Mean in Politics Now vs. When It Was Conceived?

Today, the Republican Party is still commonly referred to by its nickname, “the GOP,” which stands for “Grand Old Party.” Have you ever wondered how the political party got its nickname — and why? Well, you’re certainly not alone.

We’re taking a look back at the origins of the term and why it was first used over 150 years ago. We’ll also take a look at the history of the GOP and how it has changed since its establishment.

The Origins of the Nickname “GOP”

When the Republican Party was first nicknamed the “grand old party” — or the “gallant old party” — it wasn’t actually that old at all. The term was first used in reference to the party during the early 1870s when it wasn’t yet 20 years old. As it turns out, the GOP nickname has been around for even longer than the Republican Party as we know it today.

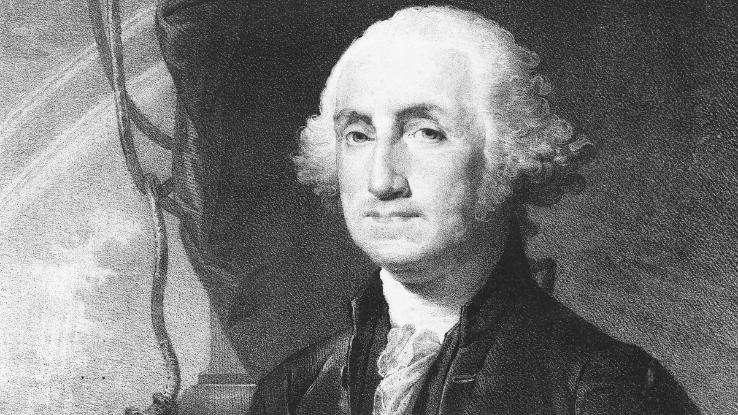

Perhaps unsurprisingly, when the Founders went about setting up the nation’s government, not everybody agreed on a single vision. For example, George Washington and Alexander Hamilton tended to favor a strong central government, while Thomas Jefferson and his supporters argued that government should play more of a background role in people’s lives.

Washington and Hamilton’s party eventually became known as the Federalist Party, while Jefferson’s became known as the Jeffersonian Republican Party — and, later, as the Democratic-Republican Party. By the 1830s, the Democratic-Republicans evolved into the Democratic Party, which still exists today. Ironically, it was they who first bore the “grand old party” nickname.

How the Republican Party Became the GOP

So, how did the GOP moniker transfer from the Democrats to the Republicans? The Republican Party was first dubbed the “grand old party” in the early 1870s due to the role it played in preserving the Union during the Civil War. The acronym “GOP” was reportedly first used by a Cincinnati-based newspaper typesetter named T.B. Dowden in 1884. Legend has it that he first chose to run a story highlighting the “Achievements of the GOP” simply because he didn’t have enough room left to spell out “grand old party” — and the acronym stuck.

The Republican Party itself was first formed back in 1854. A group of politicians from the Whig Party (which, like the Federalist Party, has since gone the way of the dinosaurs) first formed the Republican Party to oppose the expansion of slavery into new Western U.S. territories. By 1860, the issue of slavery had divided Democrats from the north and south to the extent that the Republicans were able to gain a presidential victory for Abraham Lincoln.

While the goal of the Republican Party was initially centered on stopping the spread of slavery — not abolishing it altogether — things shifted during the Civil War.

The GOP During Civil War and Reconstruction

During the war, the Republicans saw an opportunity to abolish slavery completely. President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862 and it went into effect on January 1 of the following year; of course, many formerly enslaved people didn’t receive news of the Emancipation Proclamation — or the subsequent Thirteenth Amendment, which took Lincoln’s wartime measure further, putting in place a “constitutional guarantee” of “perpetual freedom,” and, thus, abolishing slavery in all states — until after the war ended.

In recognizing the violence enacted against Black people since before the country’s founding, these policies were just the first steps when it came to creating substantive change in the United States. In fact, the fight for racial justice, equity, and liberation still continues today. But back then, in a post-war period known as Reconstruction, the newly formed Republican Party continued to align itself with civil rights efforts. At the time, this made the party far more popular in the more industrialized northeastern states, where financiers were also capitalizing on increased government spending.

As a result, the Republican Party’s association with big business began and continued to grow over the next few decades. This was also the beginning of the party’s association with the elite or rich upper-class, an association still commonly made by some Americans today.

While some Republican presidents, such as Theodore Roosevelt, attempted a more progressive approach to economic issues, things came to a head during the Great Depression. Many Americans became resentful toward the Republicans’ resistance to utilizing government aid to support struggling Americans. Ultimately, this division helped Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt gain an easy victory over Republican incumbent President Herbert Hoover in 1932.

Shifting Political Tides Post-World War II

The aftermath of World War II brought a great deal of political change for both the Democratic and Republican parties. White southerners who had previously inherited their ancestors’ hatred of the GOP began crossing the aisle to champion the Republican opposition to big government. Likewise, many Black voters, who had remained loyal to the Republican party due to its initial backing of equality and civil rights, began drifting to the side of the Democrats in the wake of the Great Depression and FDR’s New Deal.

In the later part of the 20th century, the Republican party underwent another transformation under President Ronald Reagan; Reagan’s popularity was boosted not only by his outspoken anti-communist views but also due to the support of Jerry Falwell, an anti-LGBTQ+ evangelical pastor who spearheaded what’s become known as the “Moral Majority.” To this day, the GOP is still known for its conservative stance on social issues, including abortion, reparations, LGBTQ+ rights and more.

The Republican party still attracts many voters due to its support of a smaller government and economic policies, while it attracts others due to its reputation as a vehicle of “resistance” to more progressive social reforms.

The Modern-Day GOP

It has been a rocky few decades for the GOP and for U.S. Politics in general. The 21st century began with the Republican presidency of George W. Bush, who initially gained favorable ratings for his response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. As time wore on, however, Bush’s popularity began to wane due to the onset of the Great Recession and heightening opposition to the Iraq War.

During President Barack Obama’s subsequent Democratic presidency, Republican opposition to progressive economic and social reform only heightened, resulting in the rise of several right-wing movements, including the formation of the Tea Party.

In 2016, the election of Donald Trump raised questions about the future of the Republican Party. Trump managed to construct a support base from groups who would appear to support contradictory values, at least on paper. On the one hand, he found continued support among white Christian evangelicals, while on the other he attracted various alt-right hate groups that were openly composed of neo-Nazis and otherwise racist, misogynistic, and homophobic members.

In fact, Trump’s presidency was so divisive that lifelong Republicans, and GOP figureheads, formed the Lincoln Project, which aimed to ensure Trump’s defeat in the 2020 presidential election. While this may sound counterintuitive, the founders’ motives stemmed from a distaste for Trump’s new style of Republicanism and the long-term effects it would have on their party. While some Republicans still support Trump, others consider his presidency a disaster — one marked by the rampant spread of the COVID-19 virus, Trump’s continued support of a deadly insurrection at the Capitol, and his historic double impeachment.

Whether supporters or opponents of Trump, many Americans view his presidency as among the most divisive in modern history and wonder what implications its aftermath will hold for the future of the GOP. In the end, only time will tell.