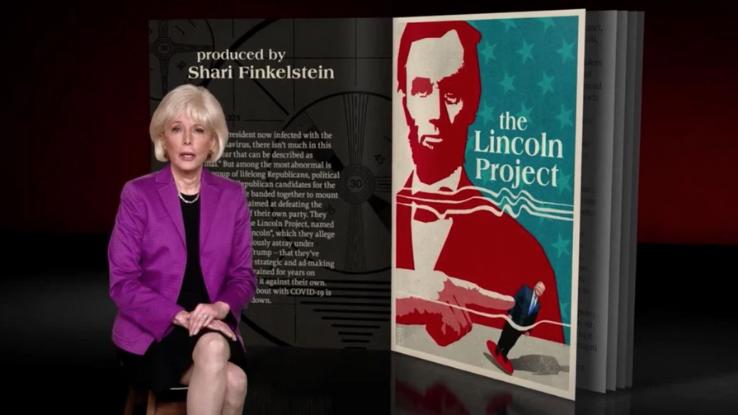

What Is the Lincoln Project — and Why Will It Matter Post-Election?

The Lincoln Project, a super PAC founded in 2019, garnered a great deal of attention during the 2020 presidential election. The group amassed 2.7 million followers on Twitter as well as an impressive following on various podcast channels. But, since its founding in 2019, the Lincoln Project has also generated everything from praise to criticism to confusion in the media. From how the political action committee captured the attention of the American public to its uncertain future, we’re giving you a crash course on the Lincoln Project.

What Is the Lincoln Project?

The timing of the Lincoln Project’s founding in 2019 was no accident. As you may know, the group was started by a number of lifelong Republicans whose aim was to defeat Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election. While this may sound counterintuitive, the founders’ motives stemmed from a distaste for Trump’s new style of Republicanism and the long-term effects it would have on their party.

The Lincoln Project’s eight co-founders include veteran political strategists, such as Steve Schmidt and John Weaver, who previously worked with high-profile, leading Republicans, from John McCain and George W. Bush to John Kasich. Other co-founders included Rick Wilson, a former media consultant for political figures like Rudy Guiliani and Marco Rubio, and conservative lawyer George Conway, the husband of former Trump Senior Counselor Kellyanne Conway.

The eight men and women banded together with the knowledge that their founding of the Lincoln Project could quite possibly mean the end of their careers as leading voices in the GOP. Nonetheless, they were driven forward by the stark differences in the behavior of President Trump and celebrated Republicans of yore. At the onset, the group stated their mission in a fairly straightforward manner: “Defeat President Trump and Trumpism at the ballot box.” But the subtext of their goal seemed to be ensuring that Trump’s behavior did not reshape the national image of the Republican party.

As co-founder John Weaver explained to 60 Minutes, “We’ve gone from caring about character, rule of law, defending the constitution, a cogent national security policy, [and] free trade. Where are all those issues? Imagine if you had traveled the country for 30 years, fighting for Republican principles, and you learn it was all a lie. No one cares about all the issues that we fought for.”

While the Lincoln Project rallied behind (now-President) Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential campaign, the group explained that their motives were less about backing a particular party and more about electing the right man for the job. As noted on their website, “Our many policy differences with national Democrats remain. However, the priority for all patriotic Americans must be a shared fidelity to the Constitution and a commitment to defeat those candidates who have abandoned their constitutional oaths, regardless of party. Electing Democrats who support the Constitution over Republicans who do not is a worthy effort.”

The Lincoln Project’s Impact

Some might argue that the very existence of the Lincoln Project went a long way in reassuring many lifelong Republicans that they weren’t alone in their skepticism of Trump. In fact, the group’s messaging urged Americans to refuse to let Trump take the Republican party in a new direction, directly calling out his less-than-flattering behavior as something that was in no way endorsed by “traditional” Republicans.

In the lead-up to the 2020 elections, the group launched a variety of bold ads, social media posts, and podcasts, which, ultimately, helped the Lincoln Project gain a more mainstream foothold. From humorous parodies to merciless attacks, the Lincoln Project sought to bring former and current Republicans — as well as Independents — across what they called “the Bannon Line.”

In an interview with AdAge, Rick Wilson explained the meaning behind that benchmark’s name. “Steve Bannon, who is no fan of us, said, early in the process, if these guys can move 2% or 3% of the Republican vote, Trump is gonna lose,” Wilson said. “Well, from the metrics we’re showing, in the swing states, where we spent I would say 80% to 85% of our resources, we moved the Bannon Line, and crossover Republican votes, between 9% and 13%.”

Despite the praise that the Lincoln Project received from many Americans throughout the election, it also picked up its fair share of critics. Some objectors on both sides of the political aisle pointed out that liberal organizers, such as Georgia voting rights activist and politician Stacey Abrams, were far more effective in generating the Biden/Harris win than the Lincoln Project and its viral ad tactics. Others suggest that the lack of a landslide win for President Joe Biden points to the Lincoln Project’s lack of effectiveness. That is, critics argue that a group that managed to raise $78 million by November 2020 should have been able to convince far more conservatives to join their cause.

What’s Next for the Lincoln Project?

The group’s aim of defeating Trump was realized in November, when the election swung in the favor of President Biden. So, where does a group that’s realized its ultimate goal go from here? This question was met with a fairly clear short-term answer when Trump’s refusal to concede the election became apparent. The Lincoln Project announced in November that they’d be taking on the two law firms who had chosen to represent the president in voter-fraud-related lawsuits. The group’s Twitter page encouraged followers to contact the two law firms and “ask them how they can work for an organization trying to overturn the will of the American people.”

In fact, even before the election rolled around, the Lincoln Project was already putting out feelers for their post-election future. On October 27th, Axios reported that the co-founders were in talks with United Talent Agency, which potentially points to the formation of a media group. The media angle may have been inspired by the past success of groups like Crooked Media, a team of former Obama staffers who launched a now-thriving media business in 2017.

Considering that the Lincoln Project already appears to have a few offers on the table, launching their own media brand may not prove to be a bad angle. After all, the Lincoln Project’s podcast garnered quite a following and remains a viable platform when it comes to retaining relevance. Axios also reported that the Lincoln Project was currently working with a documentarian/motion picture producer on a non-fiction feature film, though when the project is set for release has yet to be disclosed, and, perhaps even more surprising, the group has also reportedly attracted the attention of several unnamed TV studios, all of which expressed interest in collaborating on a House of Cards-style scripted series.

In the wake of the January 6 white supremacist attack on the U.S. Capitol — an insurrection incited by former president Trump when he encouraged his supporters to stop the official certification of the presidential election results — Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) penned a New York Post article that blamed “cancel culture” for the backlash to the insurrection. In response, Lincoln Project co-founders spoke out: Jennifer Horn called Hawley a “Traitor,” while Reed Galen tweeted at Hawley, stating, “…[Y]ou’re a constitutional lawyer. It is the right of every private citizen to redress the grievances. [The Lincoln Project] and millions of Americans hold you accountable. You may want to be a dictator but you’re not one yet.”

In an interview with WBUR, writer and political consultant Stuart Stevens noted that Trump was “right” in one regard, insofar as he “sensed that the Republican Party really didn’t believe in anything and if he came in and promised them power, they would go with a guy who was against everything they said they were for.” In the long run, it’s not yet clear if the Lincoln Project will be a necessary part of ensuring that the Republican party rejects alt-right Trumpism in the future, but it looks like the group will continue to fight to reclaim their party.