Life After COVID-19: Reflecting on How the Pandemic Changed Schools & Education in Lasting Ways

The word “unprecedented” has been thrown around a lot over the last year, but it’s hard to pinpoint another word that captures just how much COVID-19 has changed the world. For example, since March 2020, educators have found themselves in the middle of a public health crisis — and scrambling to transition their classes into online courses at the last possible moment.

At the K-12 level, most schools, especially public schools, didn’t have roadmaps to deal with all-virtual learning scenarios, despite teachers’ best efforts. Even privately funded schools and universities with seemingly huge endowments were ill-equipped to surmount technological roadblocks and or assist students who were suddenly searching for housing and support — financial and otherwise.

It’s clear that the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic extend far beyond a canceled March Madness tournament, Zoom-hosted classes, and graduation gatherings held on Animal Crossing. As the back-to-school season begins in earnest, it’s important to reflect on the myriad ways COVID-19 has impacted our education system.

How Did K-12 Schools React to the COVID-19 Pandemic?

When the COVID-19 pandemic first swelled in 2020, many students in K-12 learning environments were sent home and, for the remainder of the school year, learned from home. Given the lack of clear information surrounding COVID-19, this seemed like the most logical course of action. For example, buses and hallways to cafeterias and classrooms, schools aren’t set up to accommodate social distancing practices — and sanitizing and protective equipment, like masks or plastic shields, costs quite a bit.

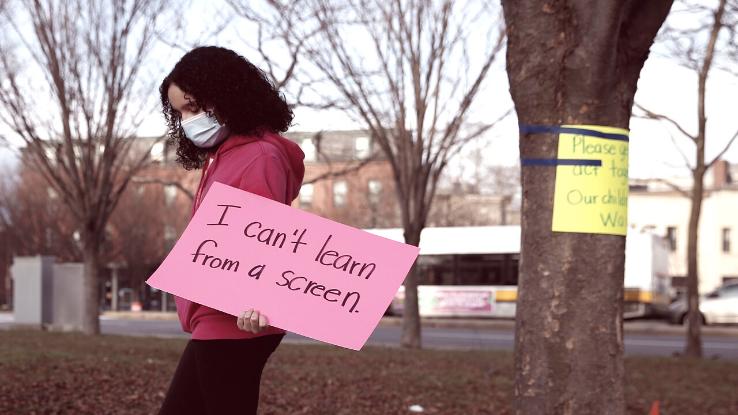

Unfortunately, however, schools’ resources are limited when it comes to supporting distanced learning as well. Although Zoom and Google Classroom are wonderful resources, they just aren’t accessible or feasible for all students, teachers and parents. Sometimes there’s just no replacement for the real deal, and, in this case, that’s in-person learning. Over the summer, in the lead-up to the 2020-21 school year, arguments broke out about the best course of action.

In New York City, for example, the decision to close public schools in 2020 was a difficult one. On one hand, keeping schools open would’ve been a health risk for students, teachers and their respective households. But, on the other hand, many students rely on their schools for resources or, simply, as places to go when their parents are at work. “Our public education system is a massive hidden child care subsidy,” Jon Shelton, a historian of the teaching workforce at the University of Wisconsin, told The New York Times.

That is, for some students, school libraries are the only places they can access online resources, books and other school materials. And for students with disabilities, where classrooms are often staffed with paraprofessionals or one-on-one aids, distanced learning poses a number of additional challenges. Perhaps most urgently, many students rely on meals from their schools; parents who can’t afford breakfast and lunch can find a partner in school cafeterias, which often offer meals to students from low-income families during the summer as well, even when school is out.

Following that line of thinking, Seattle-based bus driver Treva White and nutritionist Shaunté Fields started delivering breakfast and lunch to children and their families. Since the COVID-19 school closures, the Seattle Public Schools and Nutrition Services Department have worked to distribute meals to approximately 30,000 people per day, including on weekends. Needless to say, schools are essential parts of students’ lives and communities — even beyond learning.

How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact Students & Teachers?

When schools in New York City reopened in the fall, there was a lot of mixed messaging — and 11th-hour decisions — from local officials. Part of that may have been the rather malleable guidelines the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provided in regards to reopening, but, on the other hand, leadership across the country has waffled throughout the pandemic when it comes to reopening schools and businesses.

In the end, many schools in New York City opted for a mix of in-person and virtual learning to help mitigate the myriad concerns associated with social distancing practices. Nearby, in Stamford, Connecticut, public schools implemented alternating days of distance learning and in-person learning. With this hybrid approach, fewer students learn from home full time, which is seemingly a good way to address concerns parents may have about the quality of their kids’ education — concerns that spawned protests across the country.

But this push to reopen schools put one major concern onto the back-burner: the toll reopening would take on teachers and other educational professionals — and, of course, the risk. While the CDC has found that “most children with COVID-19 have mild symptoms or have no symptoms at all,” some have still contracted severe cases — not to mention, schools could become huge vectors for spreading the virus to students’ and teachers’ households. Disturbingly, in states that were more severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers drafted wills and obituaries ahead of the school year.

In August 2020, the White House formally declared teachers essential workers, noting that they are “critical infrastructure workers” — or, in other words, critical to the infrastructure of reopening the country and bolstering the economy. However, unlike other essential workers, teachers don’t have the training and background to mitigate all of these public health concerns, nor do they have the funding, in most cases, for PPE and other essential, virus-combating supplies. In some states, teachers are expected to receive vaccines early on in the rollout process, but this doesn’t hold true across every state, nor does it guarantee their safety.

It’s indisputable that teachers are essential members of our communities, but they are also people who, just like all of us, are navigating the horrors of this pandemic. Often, they go beyond the call of their job descriptions — even outside of the classroom. “My students have lost family members, and there’s a lot of trauma we are not addressing,” Jessyca Mathews, an English teacher at Carman-Ainsworth High School in Flint, Michigan, told Time. “When COVID hit, I had kids who were texting me in the middle of the night, and I answered them every single time.”

How Did Colleges & Universities React to the COVID-19 Pandemic?

When it comes to the closure of college campuses, folks seem more attuned to the other problems that stem from such decisions. Some full-time students who live on campus had nowhere else to go, while others faced daunting financial challenges without on-campus jobs or resources like meal plans. Some students depend on their universities for healthcare — not just insurance, but for therapy and onsite checkups. But just because there was an awareness, doesn’t mean there was an infrastructure in place to assist students.

Amid all of those frustrations was the permanent closure of some schools, particularly liberal arts colleges. In May 2020, MacMurray College in Illinois announced its closure after 174 years spent educating students — and it’s not the only liberal arts school, wanting for the endowments of larger universities, that was forced to shutter. And with as many as 44.7 million Americans owing a total of over $1.71 trillion in student loan debt, it’s clear that this model isn’t working for anyone.

“Higher education is not nimble. We are steeped in tradition, and we are not always able to move as quickly as we need to,” Beverly Rodgers, president of MacMurray College, a small, private liberal arts college in Jacksonville, Illinois, told WBUR. “There needs to be a remake of higher education as a business model, in my opinion.”

In March 2020, the CARES federal relief package allowed Congress to allocate about $14 billion for colleges and universities — an amount that the American Council on Education called “woefully inadequate.” The group’s ask? They, and dozens of higher ed organizations, believe at least $46 billion is needed.

Needless to say, colleges and universities found other ways to cope. Pine Manor College, a small private institution in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, that aims to support underserved and low-income students, merged with the much larger Boston College and the University of Akron eliminated three intercollegiate sports from its roster, resulting in a reported $4.4 million in savings, as well as six of its 11 academic colleges.

How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed Higher Education?

Unfortunately, novel coronavirus outbreaks were linked to college “fraternities, sororities and off-campus parties,” leading to stricter requirements — and consequences — for students who live on campus and attend in-person classes. While all-virtual classes would mitigate this risk (and temptation), some institutions feared that students wouldn’t be willing to shell out full tuition costs for online-only offerings.

Many colleges and universities tried hybrid approaches to cut down on large classes and account for the number of students on campus and in communal spaces at one time. The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) housed just 700 students and a few members of staff during the 2020-21 academic year. Additionally, the school also closed its campus to the public and redeployed UCLA food service workers to prepare meals for low-income families in the area (via Los Angeles Times). All of this came amid huge financial losses to the UC school system.

But, undeniably, we’ve also learned that there are some upsides to virtual learning. For example, for students who live at home, or couldn’t afford cross-country moves and housing, virtual models make college potentially more accessible and affordable. So, will the scheduling shake-ups and focus on virtual classes last longer than the pandemic? At this point, the mark the pandemic has made — and the cracks it has made more apparent — seems indelible.