COVID-19 Terms: The Difference Between Pandemic, Endemic, and More

As we continue to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, we continue to face an ever changing landscape of information — and a ton of misinformation. Be it the advice of medical experts or the guidelines set forth by your local officials, it feels important to take it all in, which can overwhelm even the most detail-oriented individuals among us.

However, if we want to fully understand our role in keeping ourselves and our communities safe, it’s important to get the terminology right. Although some brush off word choice as “just semantics,” correctly defining terms like “pandemic” versus “endemic” matters. After all, a lack of specificity can lead to misinformation — and that inaccuracy can breed panic. That’s where our quick guide to some of the most common pandemic-related terms comes in handy.

Fully Vaccinated and Up To Date

Vaccination status is becoming a significant factor in determining how people move through public spaces. Certain spaces and events are requiring individuals to prove that they are “fully vaccinated”, while others are asking that folks be “up to date” on their coronavirus vaccines.

In the U.S., fully vaccinated usually means that you have had one shot of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine or two doses of the Moderna or Pfizer vaccinations. To be up to date requires that you have received all additional booster shots recommended for your age group. This is a term whose meaning is regularly changing as booster recommendations change. The CDC has created a helpful chart, organized by age and the type of first shot you received, to help you keep track of just how up to date you are.

Self-Monitoring, Self-Quarantining, and Isolating

The difference between the terms self-monitoring and self-quarantining is really a difference of likelihood. If you have potentially come into contact with a carrier, but have reason to believe that transmission was unlikely, you should practice self-monitoring. Self-monitoring includes going about your daily life while watching for signs of the virus — cough, shortness of breath — and checking your temperature.

NPR provides a great hypothetical example: Let’s say you attended a large conference recently. Well, Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, explains that if “[t]he person speaking at the podium was later diagnosed, and you were in the audience — you’re not considered at risk.” Despite the low risk of transmission, you’d still monitor your health and check for symptoms, just in case.

In the instance that you’ve had close contact with someone that you know tested positive— meaning that you spent time unmasked with them in a close proximity, you might need to self-quarantine. Current CDC recommendations are for unvaccinated individuals to self-quarantine for 5 days after exposure, meaning that you should stay home and avoid other people as much as possible. Living with others? Try and limit that contact by sleeping in a separate room (if possible), masking in common spaces such as the kitchen and bathroom, and sanitizing shared spaces and items as frequently as possible. Currently, people who are up to date on their vaccinations do not need to quarantine, but should test after an exposure. Of course, if you or someone you live with is high risk, you might opt to quarantine out of caution.

In the hypothetical scenario above, Dr. Plescia notes, if you “had a long conversation [with that person] or that person coughed or sneezed on you… [you] would then self-quarantine.” That means self-quarantine is a step up from the more cautious self-monitoring scenario.

The next term on our list is isolation. A positive COIVD-19 test triggers isolation, which is when you eliminate all contact with others to the best of your ability. If you have to travel between home and a treatment center, wearing a mask is crucial to protect others from the virus-containing droplets you’re liable to spread. The CDC currently recommends that individuals who have tested positive isolate for at least 5 days, with longer isolation periods for people who became very sick or did not experience a reduction in symptoms after day 5. Anyone who tested positive for COVID-19 should continue to mask in public spaces for at least 10 days after symptom onset or their first positive test (whichever came first).

Pandemic, Endemic, and Epidemic

In early days scientists talked of eradicating the coronavirus, though more recently that has been dismissed as a possibility. Now that we can no longer talk about the end of the coronavirus, people are looking for other ways to describe possible futures. This is where the term “endemic” has found its footing.

An epidemic occurs when a disease spreads at high and unexpected rates throughout a population.You can think of this as meaning the same thing as “outbreak” but perhaps referring to a slightly larger population or geography. An epidemic becomes a pandemic (with the root word pan meaning “all”) when the spread of that disease happens across several countries or continents. This is to say that the coronavirus started as an epidemic in Wuhan, China, and quickly became a pandemic as the disease spread across the globe.

A disease becomes endemic when it achieves a certain, predictable baseline. This doesn’t mean that cases never rise. The flu is endemic, and we expect more flu cases in the winter months than in summer months. Right now, the emergence of new variants that behave in unpredictable ways mean that the coronavirus is still classified as a pandemic.

It’s also important to note that just because a disease has become endemic, doesn’t mean that it is harmless. In an effort to replace the idea of “the end of the pandemic” with something that also inspires hope, many have been using the word endemic in a slightly more rosy way than is necessarily accurate. Tuberculosis, for example, is both endemic and deadly. The steps that we take now still have a lot of power to shape what an endemic coronavirus will look like in the future.

Shelter-In-Place and Lockdown Orders

Shelter-in-place and lockdown orders are mitigations strategies enacted at a policy level to respond to surging case counts. While these terms tend to refer to slightly different scenarios, it’s important to note that the use of these terms has been variable in different cities and countries across the globe. Our recommendation is that you always read up on the specifics of any local orders that may affect you.

A shelter-in-place decree means that, regardless of one’s status, staying at home is a must. A step up from this scenario is often called a lockdown (sometimes also referred to as a quarantine, which admittedly, can be confusing) wherein officials place a city, county or state on lockdown, meaning travel in and out of the area would be strictly prohibited, in addition to restrictions on movement within the area.

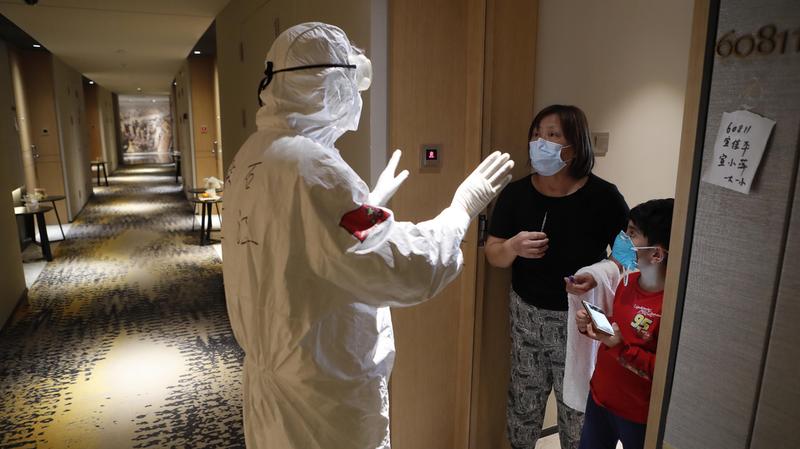

In early days of the pandemic, on March 16, 2020, officials in California’s Bay Area — which includes San Francisco and Oakland — issued a shelter-in-place order. During that time, residents were allowed to get some fresh air outside, preferably near their homes and away from others; buy groceries; pick up prescriptions; and travel to the doctor. Otherwise, they were expected to remain at home. More recently, on March 28th in Shanghai, Chinese officials enacted a lockdown. Residents were required to stay at home, and deliveries of necessary goods were left at various checkpoints in the city to assure that no one inside Shanghai came into contact with the outside world.

Although the United States didn’t implement strict, country-wide lockdowns, some international travel restrictions were put in place. However, country-wide lockdowns, which not only stopped international travel but kept residents home-bound, proved immensely successful for countries like New Zealand and Australia.

Social Distancing & Physical Distancing

Amid the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued guidelines for “community mitigation strategies” — essentially, ways to limit the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). According to the CDC, one of the most effective ways to thwart the proliferation of the virus is to practice “social distancing,” or, according to others, “physical distancing.” So, how are these terms — and practices — different from one another?

Epidemiologists use the term social distancing to refer to the conscious effort taken by individuals to reduce close contact between themselves and others, which will prevent community transmission of the virus. In practice, social distancing means keeping a safe space between yourself and other individuals who do not share your household. In both indoor and outdoor spaces, that safe distance is about 6 feet. By putting social distancing into practice — and staying away from groups of other people — you put the health and safety of others before your desire to be social, which can severely curb the number of COVID-19 cases and ensure hospitals and other facilities aren’t overwhelmed.

So, where does physical distancing come in? In essence, physical distancing and social distancing are the same practice — and the main difference stems from the kind of message the diction is sending. “Rather than sounding like you have to socially separate from your family and friends, ‘physical distancing’ simplifies the concept with the emphasis on keeping 6 feet away from others,” psychologist Dr. Shahida Fareed told Geisinger.

While it may seem like a small difference, the seemingly interchangeable terms do have different connotations and it’s important to be mindful of them, especially since the pandemic proved to be a very isolating time — a time that’s impacted folks’ mental health in an unprecedented way.