How Long Does It Take to Develop a Vaccine?

Despite the coronavirus pandemic affecting billions of people around the world, various vaccines have started making their way to the market — and hope for a slowdown in the spread of the virus is on the horizon. It’s a great reminder that modern science accomplishes amazing feats on an ongoing basis. But it’s also understandable to wonder why the process of creating a vaccine, from early development to full rollout, takes as much time as it does — particularly considering the urgency that the COVID-19 pandemic has made us all feel. The reality is that the answer is complicated.

Biotech and pharmaceutical companies like Moderna, Pfizer and Merck as well as research universities like Oxford have all launched emergency fast-track development approaches and clinical trials to create successful coronavirus vaccine candidates, but certain safeguards simply can’t be skipped throughout the development process — and that’s all in the interest of public safety. Although COVID-19 continues to take lives on a daily basis, a rushed vaccine that isn’t properly tested could ultimately prove to be just as dangerous as the virus.

Now that vaccine rollouts have started and the first recipients are getting doses of COVID-19 vaccines, it’s natural to wonder about vaccine safety and long-term health. To better understand the challenges scientists have surmounted in creating a fast, safe and effective coronavirus vaccine, let’s take a look at how long the normal development process takes and how the accelerated approval process compares.

Stages of Vaccine Development

According to guidelines established by the CDC, vaccines pass through six general stages of development: exploratory, pre-clinical, clinical, regulatory review and approval, manufacturing, and quality control. The full process is essentially the same as the process for any drug approved for use in the United States. These stages are mandated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), with its Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) division officially in charge of regulating vaccines. It’s not unusual for a vaccine to take 10 to 15 years to complete all the phases under normal circumstances.

During a public health crisis, such as the one caused by the 2020 novel coronavirus pandemic, the FDA may allow emergency adjustments to the timeframes normally associated with these stages. However, all the stages must still be completed to varying degrees, depending on the stage. In particular, the regulatory review and approval stage takes place much more quickly.

Exploratory Stage

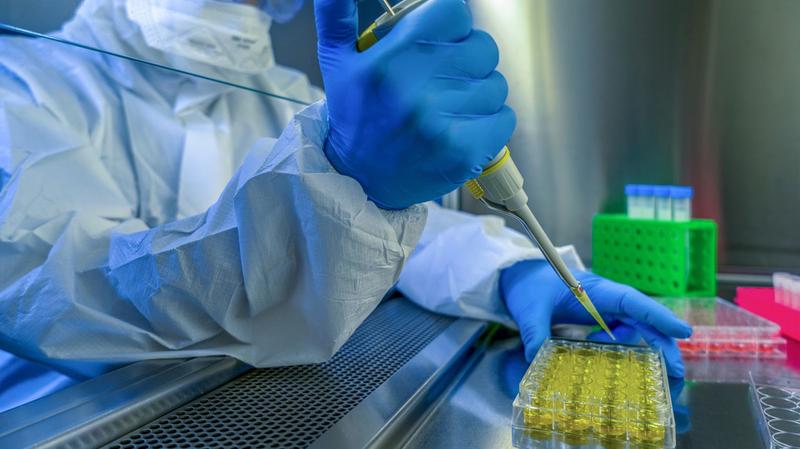

Laboratory research and testing makes up the beginning stage of vaccine development. In this phase, scientists from the academic sector, government sector or private sector try to identify natural or synthetic antigens that could either protect the human body from the target disease or at least help the body fight the disease. Different vaccine approaches can be used to establish immunity, and it takes time in this phase to determine which type will work best. For example, some vaccines contain mild strains of live virus, while others use inactive viruses to trigger immunity. The exploratory stage often takes two to four years to complete, with many vaccine ideas abandoned along the way.

Pre-Clinical Stage

Once a potential vaccine has been developed, researchers start pre-clinical studies using animal testing to evaluate the immune response created by the vaccine. Animal studies usually involve monkeys due to their biological similarities to humans but often first begin with mice or rats. As the research progresses, researchers may inject animals with the vaccine and then attempt to infect them with the target virus. The goal of the studies is to determine the potential cellular reaction humans could have to the vaccine.

Researchers also use the results in this phase to make adjustments to dosing and determine the safest delivery system — usually subcutaneous injection or intramuscular injection — for the vaccine. The pre-clinical stage is the time when researchers attempt to determine the effectiveness of the vaccine and adapt the different components to achieve the best results with the least amount of side effects. It’s common for potential vaccines to fail during this phase by not triggering immunity or causing dangerous complications. The pre-clinical stage typically lasts one to two years.

At the end of the pre-clinical stage, a sponsor — possibly a private company, government agency or research institute — submits an application to the FDA for approval of an Investigational New Drug (IND). The applicant must provide all the details and results of the laboratory testing and animal testing as well as describe future protocols for human testing, manufacturing processes and distribution. Human clinical trials cannot proceed until the FDA approves the application and an institutional review board approves the clinical protocol.

Clinical Stage: Phase 1

As with any drug, clinical development of a vaccine takes place in three phases. The first phase involves a relatively small group of healthy test subjects, usually between 20 and 100 people. Although children are often the intended recipients of vaccines, only adults participate in the earliest phase of testing. The trials are sometimes blind — recipients don’t know if their doses are real — and they sometimes involve challenge studies, which require researchers to deliberately attempt to infect subjects with the virus after giving them the vaccine. Researchers carefully control the “infection” process and closely monitor participants’ reactions. The full potency of a virus may not be used, for example.

The purpose of testing at this phase is to evaluate the immune response in humans and look for potentially dangerous side effects. If the results are positive, testing advances to the next clinical trial phase. If serious problems and risk factors are identified, researchers may attempt to adjust dosing to eliminate the problem or try to adapt the existing vaccine. In some cases, they may decide to abandon a vaccine and create an entirely new version.

Clinical Stage: Phase 2

During Phase 2 human clinical trials, researchers focus on a larger group of test subjects — usually numbering in the hundreds — that fit the criteria of the average vaccine recipient. That includes using younger test subjects for vaccines intended for children and older test subjects for those intended for the elderly. The trials are controlled, random and use a placebo vaccine for some participants.

Phase 2 continues to focus on the overall immune response of test subjects as well as the severity and prevalence of side effects. It also attempts to pinpoint the most common side effects across the larger group of people. More attention is also paid to the vaccine’s delivery method at this phase to determine if effectiveness could be improved by altering how the vaccine is administered.

Clinical Stage: Phase 3

By the time it reaches a Phase 3 clinical trial, a vaccine has already proven its effectiveness — and its potential side effects — among a few hundred people, but it’s still important to learn whether those results can be considered reliable among the larger population. Phase 3 trials usually involve thousands of people. Testing protocols are random and double blind — neither researchers nor participants know if doses are placebo — at this phase. Placebos could be anything from saline solutions to other helpful vaccines.

Phase 3 offers many benefits in the final stages of the vaccine’s development, including allowing researchers to discover rare side effects that might only occur once in a group of 10,000 people, for example. This allows health officials to better prepare for every potential outcome of receiving the vaccine. At this phase, researchers hope the end result is a vaccine that effectively prevents the disease by producing protective antibodies while only causing minimal, mild side effects.

Regulatory Review and Approval

After completing the final phase of human clinical trials, researchers can submit a Biologics License Application (BLA) to the FDA to request approval to produce the vaccine and distribute it. A special team of scientists and medical professionals at the FDA will evaluate the results of all the clinical findings in all the previous trials and make an approval decision based on the risks versus the benefits of the vaccine. Before making a final decision, they also order an inspection of the factories that will produce the vaccine. Labeling for the vaccine also follows strict guidelines and requires approval.

Upon FDA approval, the sponsor submits the approval to the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) for review. This committee consists of scientists and medical professionals who don’t work for the FDA that offer an independent review of the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine.

Vaccine Manufacturing

FDA monitoring of the vaccine doesn’t end when a license is issued for a vaccine. The agency monitors the manufacturing process and the manufacturer’s testing protocols to ensure safety by making sure vaccines aren’t contaminated and deliver consistent potency. Manufacturers are always subject to facility inspections, and the FDA can also conduct its own testing on vaccine samples at any point.

Manufacturers start developing their factory designs and manufacturing protocols for large-scale production after vaccines make it past Phase 1 clinical trials and a portion of Phase 2 clinical trials. Once company leaders have sufficient evidence to conclude the vaccine could be successful, manufacturing planning begins to ensure factories are ready to be inspected and move into production when the time comes.

Quality Control

In addition to ongoing facility inspections and vaccine testing, various protocols are put in place to ensure the ongoing quality and safety of vaccines after their approval. In some cases, researchers may choose to continue with Phase 4 clinical trials, usually for the purpose of determining other potential uses for the vaccine or to pinpoint ways to further enhance its effectiveness or eliminate side effects.

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) tracks and monitors side effects of all the different vaccines and provides all that information on an easy-to-use website established by the CDC and FDA in 1990. According to the CDC, the goal of the site is to track adverse events associated with different vaccines to zero in on potentially serious problems. VAERS receives about 30,000 adverse event reports each year, with 10% to 15% of the events serious enough to require hospitalization for life-threatening illnesses or even disability or death.

When events are reported, the CDC investigates to determine if a vaccine could have caused the event. In many cases, other mitigating factors are to blame. They also routinely evaluate VAERS information to uncover rare adverse reactions as well as track the frequency and severity of known side effects. This information also allows scientists to detect unusually problematic vaccine batches and make connections to potential risk factors for certain side effects. Of course, most people don’t report minor adverse events like swelling at the injection site, which makes fully accurate tracking impossible. Serious adverse events are more likely to be reported, particularly right after a vaccination when the connection seems obvious.

Also established in 1990, Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) consists of a series of linked databases containing medical records and vaccine information, including details related to adverse reactions to vaccines. The information comes from medical practices and not from randomized, controlled, blind trials, which makes it a little harder to evaluate the data, but it’s still a useful tool in monitoring real-time data to compare adverse event rates in recently vaccinated people to rates in unvaccinated people.

Emergency Protocols and Approvals

As soon as the world really understood the reality of the novel coronavirus pandemic and the threat it posed, the CDC, the World Health Organization (WHO) and other health institutions around the globe were bombarded with questions — and demands — about how long it would take to develop a vaccine for the virus. Hearing that a vaccine following a normal track could take more than a decade to reach the market felt alarming in the midst of the pandemic’s urgency after case numbers and death tolls had been climbing rapidly.

In the United States, when faced with an urgent public health crisis, the FDA recognizes the need to loosen some of the normal restrictions to speed up the typical timeline for vaccine development. But, in the case of COVID-19 vaccines, that hasn’t meant companies and research institutions could completely disregard the rules or the typical evaluation timeline. When the world needs a vaccine quickly, one that causes dangerous health risks of its own won’t help the situation, which is why a modified testing process comes into play.

To carefully balance the urgent need for an effective vaccine and the need for that vaccine to be safe, pharmaceutical companies engaged in carefully designed — but accelerated — development, testing and clinical trials. The FDA has facilitated this process by processing Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs), which are provisions that allow the agency to make products available that haven’t gone through their typical full testing and approval processes. EUAs are granted during public health emergencies for unapproved treatments when approved treatments don’t yet exist. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and Moderna that have developed vaccines have been applying for EUAs to allow those treatments to be utilized on an emergency basis.

Although EUAs grant authorization to previously unapproved vaccines, those treatments still have to undergo rigorous testing and clinical trials — they’re just not as long as they’d typically be during a normal approval process because some of the review process is shortened. And they still need to meet certain benchmarks that help determine their safety before they can make their way to the public. The vaccine must still go through the progressively detailed and extensive phases of testing that ultimately see tens of thousands of people participating in the clinical trials. This is to effectively determine how the vaccine candidates affect people’s immune systems and to gather enough data about a sample of people who represent the U.S. population. Study participants also come from a wide range of demographic and age groups and have varying health statuses — factors that help researchers determine how the vaccine might affect different people in different ways, along with the early side effects that may arise in some populations.

Because of the faster-than-normal process that today’s COVID-19 vaccines have gone through to obtain EUAs, additional studies will be conducted to discover more about the long-term effects of the vaccines, the full duration of immunity they provide and the potential long-term side effects they might cause. Due to the accelerated process many of the vaccine candidates are cycling through before emergency approval, developments are changing rapidly. But with the progress pharmaceutical companies have made, including Pfizer and Moderna’s applications for EUAs, the future of American public health in relation to the COVID-19 crisis is finally starting to look brighter.