“A Return to Normalcy”: How a Campaign Slogan Became Part of Our Pandemic Lexicon

In the wake of a pandemic that’s been going on for about 19 months, a so-called “return to normalcy” sounds pretty great to many Americans. While we’re all throwing around buzzwords and phrases, like “normalcy” and the “new normal,” this notion is far from new.

In fact, it was first coined as a campaign slogan back in 1920 — a time that’s not completely unlike the one we’re living through today. So, where did the “return to normalcy” concept come from — and is it really what we need post-COVID-19 pandemic?

The Eerily Familiar Issues of 1920

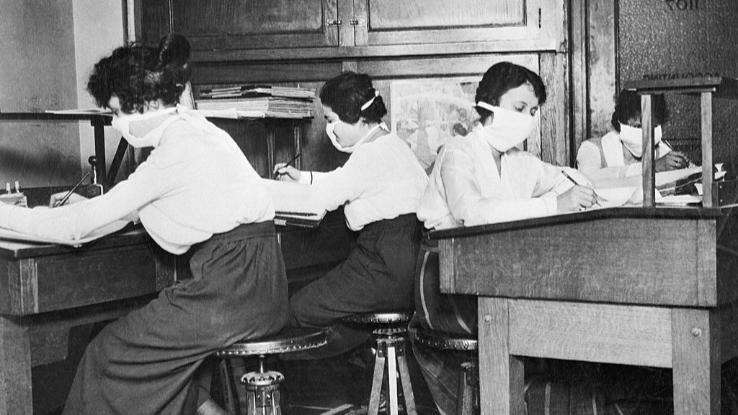

While 2020 was deemed an “unprecedented” year on a rather continuous basis, the same can be said for 1920 — or, in the very least, the years leading up to it. World War I, which claimed ____ lives, finally ended in 1918, but the horrors didn’t end. That same year, the flu pandemic of 1918 killed 675,000 Americans. Globally, the pandemic infected “one-third of the planet’s population” and killed tens of millions.

In America, racist mobs committed horrific acts of violence, murdering thousands of Black Americans. In 1919, this time in history was referred to as the “red summer,” an epidemic of white supremacist violence that led to the Tulsa Race Massacre just two years later. Fights for labor rights and reproductive rights swept the nation. Meanwhile, the “red scare” set off a string of violent raids, including the Palmer Raids. These police-led raids actually led to the creation of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

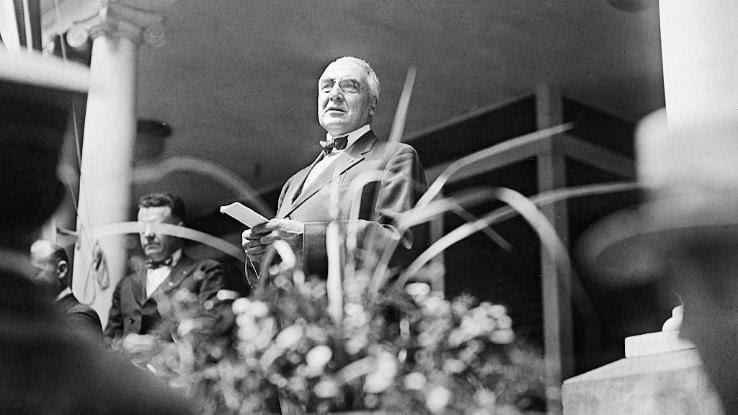

Needless to say, Americans found themselves fighting many of the same battles we are waging today. And, as the 1920 presidential election loomed, the Republican party nominated Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding as the GOP candidate. When developing their strategy, Harding and his campaign staffers wondered what American people really wanted for their country. In the wake of the nation’s — and the world’s — many ongoing horrors, the word “normalcy” came to mind.

“A Return to Normalcy” Becomes a Slogan

Over the last almost two years, we’ve all had moments of wishing things would go back to how they were pre-pandemic. (At least from a public health standpoint.) As Harding put it at the time, “America’s present need is not heroics but healing; not nostrums but normalcy; not revolution but restoration… not surgery but serenity.”

Rather than tour the United States making speeches and kissing babies, Harding conducted a front-porch campaign from his home in Marion, Ohio. Thousands of voters from across the country flocked to Harding’s lawn to hear him promise a “return to normalcy.” Harding did make some attempt to differentiate his proposal from going backward as a nation, noting, “By ‘normalcy,’ I do not mean the old order, but a regular, steady order of things… I don’t believe the old order can or should come back, but we must have normal order, or, as I have said, ‘normalcy.'”

It sounds a bit like word salad, doesn’t it? Well, after years of war, violence, and disease, many Americans were captivated by Harding’s small-town charm. In the end, he won a landslide victory over James Cox, becoming the country’s 29th president.

Normalcy’s Grammatical Grey Area

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the promise of “normalcy” has cropped up in headlines. Even President Joe Biden has used the term in an attempt to steer the country toward a pre-pandemic state. But, since Harding first popularized the word back in 1920, many Americans can’t help but wonder: Is “normalcy” even a word?

Harding wasn’t necessarily known for his eloquence, but he did address this issue directly. “I have noticed that word caused considerable newspaper editors to change it to ‘normality,'” he once told the press. “I have looked for ‘normality’ in my dictionary, and I do not find it there. ‘Normalcy,’ however, I find, and it is a good word.” While both terms are commonly included in today’s dictionaries, the results of Harding’s grammatical research are something we’ve all kind of come to accept.

But Is “Normalcy” What We Really Need?

After over a year of sheltering in place, masks wearing, and social distancing, a so-called return to normalcy sounds pretty good to many Americans. But while the goal of returning to a pre-pandemic world public health-wise makes sense, it’s important to note that many of the other issues plaguing the country today resemble those from the 1920s. That is to say, returning to the “status quo” shouldn’t be the aim in other areas.

While Harding did attempt to advocate for civil rights as president, his efforts largely fell flat. In fact, the first iteration of the Civil Rights Act wasn’t signed into law until 1964. So, despite the horrific, white supremacist mobs in Tulsa and elsewhere, nothing was really done to tackle the root of systemic racism in this country. Today, white supremacist racism still undergirds institutions in the U.S., from healthcare to policing — hence the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.

Additionally, economic inequality continues. Many Americans are saddled with insurmountable student debt. The climate crisis shapes our lives daily. Across the country, laborers are striking and protesting, demanding better workplace conditions and wages. And, in the aftermath of Texas’ radical abortion ban, Americans are taking to the streets to demand reproductive rights. Not to mention, the COVID-19 pandemic has killed more Americans than the 1918 flu pandemic.

With the country’s stark political divide — and trust in the media and authority figures shaken — it’s clear that going back to how things were isn’t an option. And it shouldn’t be the aim, either. In some ways, Harding delivered on his promise of a return to normalcy, but his campaign vow also set the bar low, perhaps stymying the possibility of creating real, effective change in a country that’s desperately needed it — and still does.

Will America repeat the same mistakes as the country moves closer to a post-COVID-19 world, or will this be the nation’s chance to establish a better, more equitable standard of normalcy? Only time will tell.