The Creation of Labor Day: A Brief History of the Labor Movement in the U.S.

In the United States, the first Monday of September marks Labor Day — and, for many of us, that’s synonymous with a fun three-day weekend. However, with the Great Resignation still in the news, the dramatic rise in unionizing efforts across the country, and 2021 being declared the Year of the Worker, you may be thinking about Labor Day with some new curiosity this year. While enjoying this end-of-summer break is a must if you have the privilege of taking time off, it’s also important to understand the story behind the federal holiday. It’s not just a day for rest, but also a day for reflection and action.

With this in mind, let’s rewind the clock and look into the history of the labor movement, which not only inspired this holiday, but made Labor Day something to celebrate beyond BBQs and beach days.

The Grim Conditions That Inspired Revolution

While the eight-hour workday seems like a given to many workers today, it wasn’t always an industry standard. Unfortunately, back in the late 1800s, working just eight hours a day felt like a pipe dream. In fact, at the height of the Industrial Revolution, people of all ages could expect to work an average of 12 hours a day, six days a week.

Despite the long hours — often in unsafe or miserable conditions — workers’ labor resulted in little more than the absolute minimum amount of money they needed to feed their families. In some cases, workers struggled to do that on their dismal wages. To make matters worse, children as young as five often worked factory jobs and, although they made a fraction of their adult counterparts, their contributions were deemed necessary.

Ultimately, this proved unsustainable — and, especially when it came to child labor, unethical. Workers no longer wanted to spend a majority of their lives working, especially not for unfair pay and in unsafe conditions. Needless to say, change was in the air.

The Rise of Labor Unions

While labor unions had technically existed in the U.S. since the late 1700s, it wasn’t until the late 1800s that they really began to ramp up their efforts and champion the voices of workers. As more workers began to realize that unions offered power in numbers, they began to join in the fight, often organizing strikes and rallies.

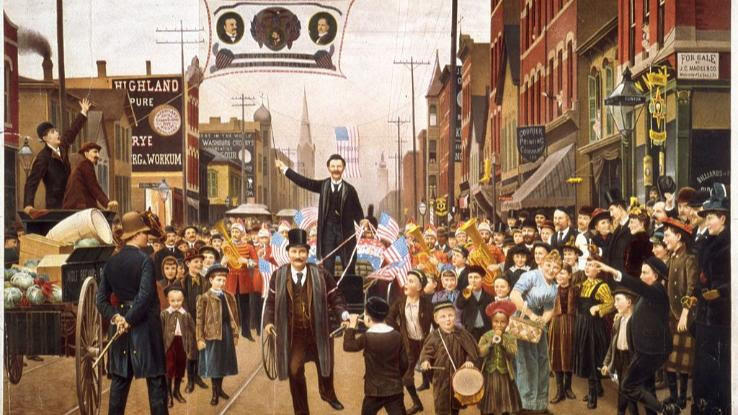

The first Labor Day parade took place on September 5, 1882: 10,000 laborers all marched from city hall in New York City to Union Square, proclaiming the day “a general holiday for the workingmen of this city.”

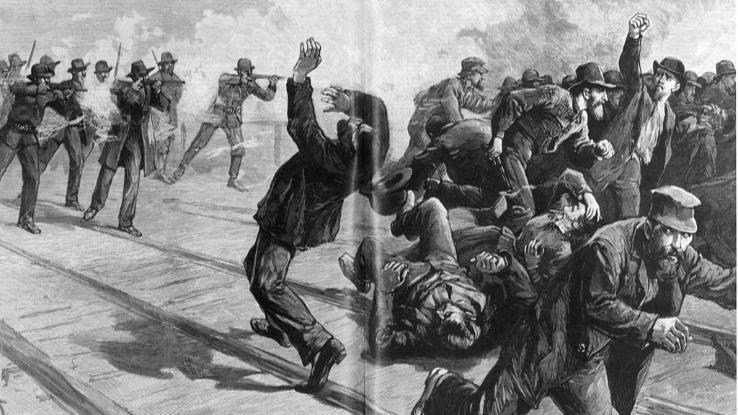

Not all of the rallies organized during this turbulent era of American history ended peacefully. On May 4, 1886, a rally in Chicago turned into an all-out riot as tensions rose between the protestors and the police, who were quick to meet the workers with violence. By the time what’s now known as the Haymarket Affair ended, eight people had died near Chicago’s Haymarket Square. Today, the event is often commemorated, referred to as “International Worker’s Day,” or “May Day.”

The Pullman Strike

As tensions continued to mount, things once more came to a head when a businessman named George Pullman made a series of poor choices. Pullman was the owner of a railroad car company called Pullman Palace Car Company. In 1893, he decided to lay off about 30% of his workers; Pullman cut the wages of the workers who remained on his payroll and refused to lower rent prices in the town where a majority of his employees lived.

By May of 1894, Pullman’s workers went on strike. Soon enough, the workers garnered sympathy, even from those in power, and their cause was seen as just. In June of the same year, Eugene V. Debs, the leader of the American Railway Union, declared a boycott on any trains that should dare to use Pullman’s cars. The result was swift; rail traffic across the country ground to a halt.

The first days of July would mark a turning point in American history. President Grover Cleveland sent federal troops to Chicago to allegedly keep protestors in line. However, the increased military presence — to no one’s surprise, except maybe the president’s — had the exact opposite effect. On July 16 and 17, protestors rioted, destroying hundreds of railway cars to express their ongoing frustration in the face of injustice.

Labor Day Becomes a National Holiday

President Cleveland actually signed Labor Day into law on June 28, 1894 — just days before ordering troops to advance on Chicago and break up the Pullman strike. In this sense, making Labor Day a federal holiday seemed more like a gesture than anything else.

But the federal government’s performative gesture was still far behind the efforts of several state governments. Oregon was actually the first to pass state legislation that recognized Labor Day in February of 1887. By the end of the same year, Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York had also solidified Labor Day as a holiday in their states. By the time the federal government caught up in 1894, over 25 states had already legally recognized the holiday.

So, who came up with the holiday idea in the first place? It’s a little unclear, though historians have generally narrowed it down to two candidates — Peter J. McGuire and Matthew Maguire. The two men were highly active in different labor unions and, because their last names were pronounced similarly, folks often confused the two activists.

The Road to a 40-Hour Workweek

Of course, recognizing Labor Day as a federal holiday was far from the end of the struggle for workers’ rights. Many Americans continued working up to 100-hour shifts and six-day work weeks well into the 20th century.

So, what other significant milestones occurred after the labor movement became more mainstream? Here’s a rough breakdown of the series of progressions that led to labor rights as we know them today:

- September 3, 1916: Congress passed the Adamson Act, which limited the workday to 8-hours but only for railroad workers. In 1917, the Supreme Court court constitutionalized it.

- September 25, 1926: Ford Motor Company took the bold leap of instituting a five-day, 40-hour workweek for their employees.

- June 25, 1938: The Fair Labor Standards Act was passed by Congress, officially limiting the workweek to 44 hours.

- June 26, 1940: The Fair Labor Standards Act was amended by Congress, changing the official workweek to 40 hours (with the exception of paid overtime).

- October 24, 1940: The Fair Labor Standards Act officially went into effect and the 40-hour workweek began to become the norm.

Even today, the fight for labor rights continues as workers, unions and activists work toward securing equal pay, shorter work weeks, and better benefits and protections, among other things, for employees across all industries in the U.S.