The History Behind Harriet Tubman’s Journey to the $20 Bill

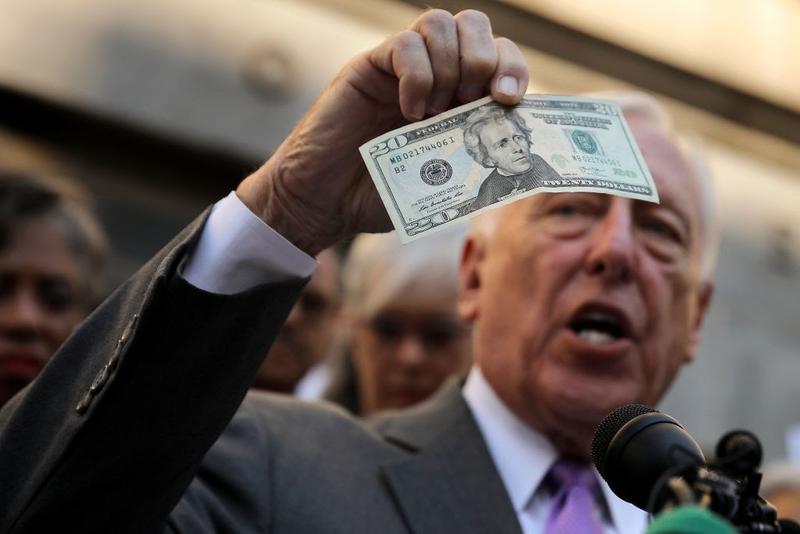

On January 25, 2021, just five days into the Biden-Harris administration, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki announced that “The Treasury Department is taking steps to resume efforts to put Harriet Tubman on the front of the new $20 notes.” This comes after the Obama-era initiative to replace Andrew Jackson with Harriet Tubman on the $20 note, originally scheduled to be completed in 2020, had been delayed by the Trump administration.

The Biden-Harris administration’s push to get the currency redesign back on track, along with President Biden’s day-one executive order aimed at promoting racial equity, is an accurate reflection of the distinct ideological divide between the two administrations. In 2019, then-Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin declined to move the project forward, claiming that “counterfeit issues” were to blame for the delay. Trump himself chimed in to downplay the redesign effort as “pure political correctness.”

Directly countering the former administration’s obstructionist dismissals of the project, Press Secretary Psaki stressed in her January 25 statement, “It’s important that our…money reflects the history and diversity of our country, and Harriet Tubman’s image gracing the new $20 note would certainly reflect that.”

Despite the deeply divided, partisan and turbulent nature of U.S. politics and society today, Americans largely seem to agree that working against racism of all types is one of the country’s most important challenges. According to a Monmouth University Poll released in June 2020, 76% of Americans polled agreed with the statement that racism and discrimination are a “big problem” in the U.S. So while representation of Black Americans, like Harriet Tubman, on our currency feels in some ways like the absolute least we can do to combat racism, it is a valuable, and necessary, step in the right direction.

Who Was Harriet Tubman?

Born into slavery in Maryland in the early 1820s, Tubman was an abolitionist, women’s rights activist and Underground Railroad “conductor” who provided safe passage to dozens of enslaved people after escaping from slavery herself at age 27.

After escaping to Philadelphia in 1849, Tubman, who described slavery as “the next thing to hell,” returned to Maryland 13 times between 1850 and 1860 to help rescue enslaved people, including Tubman’s siblings and relatives. Said Tubman, “I was the conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can’t say — I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.” Her tireless work rescuing enslaved people earned Tubman the nickname “Moses.”

During the U.S. Civil War, Tubman worked as a spy, scout, nurse and guerilla soldier for the Union military. Disguising herself as an elderly woman, Tubman entered Confederate-occupied towns and communicated with enslaved people to gather knowledge of Confederate troop movements and supply lines, relaying the intel back to Union generals. The Union military also benefited from Tubman’s deep knowledge of tunnels and routes used by the Underground Railroad.

In the years following the Civil War, Tubman met suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, began attending women’s suffrage meetings in Geneva, NY, and went on speaking tours to New York, Boston and Washington, D.C., in support of women’s voting rights. Despite never learning to read or write, Tubman earned a reputation as an eloquent and exemplary orator, speaking about her experiences escaping from slavery and rescuing others on the Underground Railroad, to argue in support of respect and equal rights for Black and white women alike.

Late in her life, Tubman settled in Auburn, NY, where she opened a rest home for elderly Black citizens and worked with local writer Sarah Bradford to write her biography, Harriet Tubman: The Moses of Her People.

The Obama Administration’s Push to Add Tubman to the Bill

The idea to feature Tubman on the $20 bill got its start in 2014, when then-President Barack Obama received a letter from a girl in Massachusetts proposing that U.S. bills feature women from U.S. history. While notable women such as Susan B. Anthony, Hellen Keller and Sacagawea have made appearances on U.S. coins, paper bills currently in circulation only feature men, the letter’s writer pointed out.

In 2015, the U.S. Treasury Department began soliciting ideas from the public to determine who should appear on the currency, and the plan to include Tubman on the $20 note was officially announced in April 2016. The new bills were meant to debut in 2020 to commemorate the centennial of the adoption of the 19th amendment, which gave (mostly white) women the right to vote, and the bills were expected to be widely available to the public by 2026.

How Often Do Currency Portraits Change?

Portrait changes on U.S. bills are relatively rare — the last update occurred in 1929, when Alexander Hamilton was placed on the front of the $10 bill. The release of $20 bills featuring Tubman will mark the first-ever appearance of a Black woman on U.S. currency.

There are several laws and regulations that govern who can appear on U.S. currency. No living person is allowed to be featured on U.S. currency. There is only one rule that stipulates a specific portrait: $1 bills are legally required to feature George Washington. Currency law gives the Secretary of the Treasury full authority over currency redesigns and updates — giving the department final approval rights over any proposed portrait changes.

Currently, the following portraits appear on U.S bills:

- $1 — George Washington

- $2 — Thomas Jefferson

- $5 — Abraham Lincoln

- $10 — Alexander Hamilton

- $20 — Andrew Jackson

- $50 — Ulysses S. Grant

- $100 — Benjamin Franklin

Why Replace Andrew Jackson?

Jackson’s portrait on the $20 note has been the subject of sharp criticism from historians and the public alike due to his status as a slave owner and his leading role in the Trail of Tears. Jackson (along with Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, who also appear on U.S. bills) was a slave owner, and brought enslaved people to the White House from his family’s plantation, The Hermitage, when he became president in 1829. Historians believe that the renovations and improvements Jackson made to the White House during his tenure as president were completed using slave labor.

In 1930, Jackson signed into law the Indian Removal Act, which gave his administration the legal right to relocate Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River to land obtained during the Louisiana Purchase. In the winter of 1831, the U.S. Army invaded the Choctaw Nation’s land, forcing them to leave the region where their families had resided for generations, and walk, on foot, with no food, supplies or water, to present-day Oklahoma. Over the next decade, the federal government forced tens of thousands of Native Americans to relocate west of the Mississippi — most often using deadly, forced marches following a route that has come to be known as the “Trail of Tears.” These marches, which spanned over 1,000 miles and caused the deaths of thousands of Native people, are today widely regarded as genocide.

How Soon Will the New Notes Be in Circulation?

While Press Secretary Psaki wasn’t able to provide a timeline for the bill’s redesign, she reassured the press that the White House is “exploring ways to speed up” the project. Janet Yellen, President Biden’s pick to head the Treasury Department, as well as the first woman to hold the post of Secretary of the Treasury in the department’s history, will oversee the project.