What Is the DACA Immigration Policy?

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) is a United States immigration policy that allows individuals who immigrated to the U.S. as children to receive deferred action on their immigration status for two years at a time. In September 2017, the Trump administration announced its intention to cancel DACA, threatening the livelihoods of 800,000 individuals in the program, but, in June 2020, the Supreme Court blocked Trump’s numerous attempts to end DACA. Now, we’re taking a look at the history of the DACA program, from how it was passed to the challenges it faced.

How the Policy Was Passed

Established in June 2012, DACA was introduced by the Obama administration as a way to prevent the deportation of young immigrants in the U.S. who lack citizenship or legal status. The program protects recipients for two years and allows them to stay in the country to work and attend school.

For years, the administration and Congress couldn’t agree on how to protect young immigrants. Plus, the Dream Act failed to pass. As a result, DACA was made through an executive order, but some states, including Texas, believe Obama abused his power in creating the program, which caused numerous problems for DACA since its implementation.

Challenges Faced During the Trump Administration

As with any policy, not everyone is in favor of DACA. Critics raised several issues with the policy. Some claimed that DACA was an insufficient short term solution to the larger issue of immigration in the U.S. While DACA provided a temporary reprieve from deportation, it did not give those enrolled a path to citizenship. Additionally, some critics asserted that the policy would encourage more minors to seek illegal entry into the U.S.

Starting in 2017, the Trump administration took steps to end DACA: First, the administration barred new applicants from the program, though, thanks to rulings in the lower courts, longstanding recipients were allowed to renew without being impacted by the administration’s agenda. In June 2020, the Supreme Court ruled that the Trump administration had unlawfully tried to cancel the program, though that didn’t completely stop Trump and the Department of Homeland Security from continually attacking DACA throughout the president’s remaining time in office.

Who Are the Recipients of DACA?

DACA recipients are currently in their mid-20s and late-30s. Many of the recipients come from Mexico and Central or South America, such as El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. Thousands also arrived from the Caribbean and Asia, generally South Korea and the Philippines.

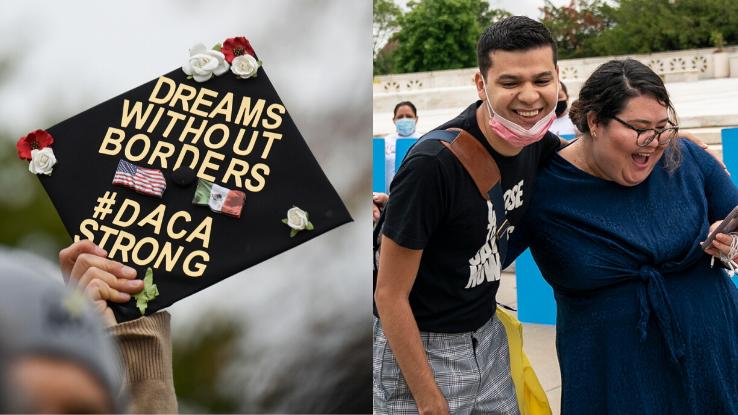

The recipients, who are known colloquially as Dreamers, live throughout the country, with the largest populations of Dreamers residing in California, Texas, New York, Illinois and Florida. The phrase “Dreamer” is based on the 2001 Dream Act, which didn’t pass, but certainly helped set the stage for DACA.

Who Is Eligible for the Program?

In order for individuals to be eligible to participate in the program, they must be younger than 31 years old as of June 15, 2012, the date the policy was announced by the Director of Homeland Security. Additional age requirements specified that DACA applicants must be at least 15 years old at the time of their request.

DACA policy requires applicants to have continuously lived in the U.S. at least from June 15, 2007, until the date of their application. Applicants are also required to have been physically present in the country on both June 15, 2012 and the date that they made their request for deferred action. Furthermore, applicants are required to be currently enrolled in high school, recent high school grads, or honorably discharged from the U.S. Coast Guard or other Armed Forces. A record free of both felony convictions and significant misdemeanors is also required for entry to the program.

The Benefits of Being a Dreamer

Participants in the program have experienced both greater employment opportunities and decreased fears of deportation from the U.S., according to the American Psychological Association (APA). The program also allows younger participants to take part in age-specific milestones along with their peers, such as obtaining a driver’s license and a work permit.

Depending on the employer, DACA recipients can also obtain health insurance. With a permit to work, they can afford to pursue higher education on top of being eligible for educational grants and loans, at least in some states. Every two years, the recipients can reapply for the program.