6 Times Civil Disobedience Changed the Course of U.S. History

We’re all familiar with the concept of disobedience — defying and questioning authority figures is something most humans start doing in childhood. Civil disobedience takes the concept of breaking the rules to a very adult level by focusing on breaking laws — but in a nonviolent manner and for a worthy cause.

In most cases, civil disobedience consists of protests that are organized to shine a light on social injustice or laws that are biased or violate our human or legal rights as American citizens. It has been used as a successful tool to inspire positive change many times throughout U.S. history. Today, the Black Lives Matter movement is poised to go down in history as another positive example of a civil movement that spawned real social and legal changes. Let’s take a look at some of the most notable times civil disobedience paved the road to change in our country.

The Boston Tea Party – 1773

One of the most famous historical acts of civil disobedience in American history actually took place before our nation was officially a nation. The not-so-festive Boston Tea Party occurred on the evening of December 16, 1773, when a group of rebellious colonists who were fed up with the unfair taxation practices of the British monarchy decided to make a statement that even a king couldn’t ignore.

A group of prominent patriots known as the Sons of Liberty — John Hancock, Paul Revere, Samuel Adams and Patrick Henry among them — denounced Britain’s policies on taxation and protested the arrival of three British East India Company ships that were loaded with tea and docked in Griffin’s Wharf in Boston. When the governor ignored their protests and demanded the tariff be paid for the tea, the men refused and hatched a plan of their own. Disguised as Native Americans, members of the Sons of Liberty and other patriots boarded the three ships and dumped 342 chests of tea into the harbor, a rebellious act that ultimately helped lay the foundation for the American Revolution.

The Night in Jail of Henry David Thoreau – 1846

Prominent American author Henry David Thoreau is famous for his love of nature, but he cared about some political issues as well. In 1846, Thoreau disagreed with America’s war with Mexico, viewing it as an attempt by the country’s leaders to add more slave territory to the nation. To express his disagreement with the nation’s actions regarding Mexico, he refused to pay his poll tax and was arrested.

The writer only spent a single night in jail, but that night inspired a lecture and essay titled “Civil Disobedience” that outlined the concept of large groups using peaceful methods to protest unfair laws and injustice. He vehemently insisted that governments would be forced to pay attention and give in to the pressure of public opinion if people would stand together and protest.

Thoreau’s action certainly wasn’t the first act of civil disobedience in America, but it was one of the most important. He didn’t stop the war with Mexico or change any tax laws, but the story of his protest and his arrest spread far and wide. Today, the influence of Thoreau’s writing on the development of civil disobedience as a tool for change is widely recognized far beyond the shores of America. Perhaps the most prominent example is when Mahatma Gandhi used these nonviolent tactics to liberate India from Britain.

Montgomery Bus Boycott – 1955

Most Americans are familiar with the inspirational story of Rosa Parks, an African American woman in Montgomery, Alabama, who went to jail on December 1, 1955, for refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white man. However, they might not know about the momentous event in the Civil Rights Movement that followed her arrest. Racially biased Alabama state and city laws called for segregation on public transportation at the time.

After Parks’ arrest, the NAACP and various African American activists, including a young Baptist minister named Martin Luther King Jr., called for a boycott of Montgomery buses that began on December 5, 1955. Approximately 70% of Montgomery’s bus riders at the time were African American, and the city was quickly deprived of thousands of dollars in lost bus fare revenue. After almost a year of boycotting, the U.S. Supreme Court declared Alabama’s segregation laws unconstitutional under the equal protection clause of the 14th amendment.

On December 20, 1955, Martin Luther King Jr. called for an end to the boycott, and African Americans resumed riding the city’s buses the next day. The successful bus boycott served as the first significant victory in the Civil Rights Movement and laid the foundation for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As a result, Rosa Parks is often referred to as the “mother of the civil rights movement.”

The March on Washington – 1963

Officially named the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the civil rights march through the streets of Washington D.C. to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial consisted of approximately 250,000 protesters. The massive event was organized jointly by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference under the guidance of Martin Luther King Jr., who wanted to lead a protest in D.C. for civil rights, and A. Philip Randolph, an activist who wanted to protest to secure equal job rights for African Americans.

On August 28, 1963, the participants arrived at their destination and listened as some of the greatest speakers of the era delivered life-changing motivational speeches that demanded social change and equal rights for African Americans. Randolph closed his opening speech with a promise that the people gathered there were just the beginning, and they wouldn’t stop until they achieved total freedom. King closed out the day with his inspirational and unforgettable “I Have a Dream” speech.

The end result of the march was the revival of stalled negotiations on a Civil Rights Act, which finally passed into law on July 2, 1964, as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The law ended public segregation on a national level and made it illegal for employers to discriminate against applicants based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin. It was a monumental win for African Americans that was followed about a year later by the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

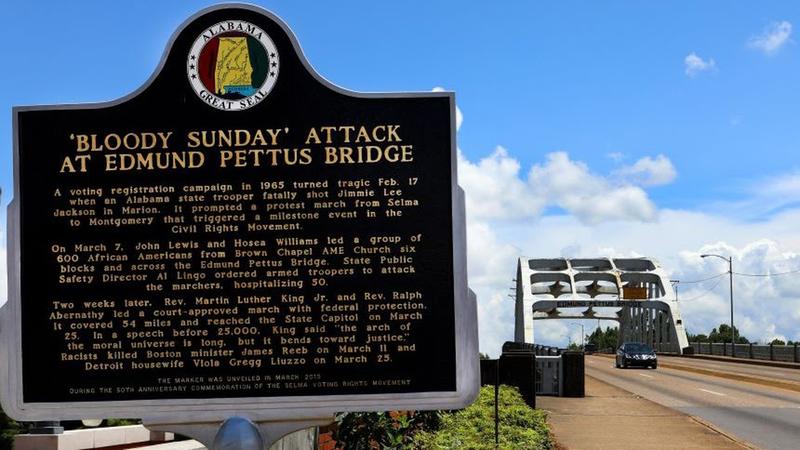

Selma to Montgomery Marches – 1965

In Alabama, three Selma to Montgomery marches were attempted to peacefully protest the violation of African Americans’ voting rights and demand the governor implement changes. The first attempt occurred on March 7, 1965, and ended in tragedy when Alabama state troopers violently attacked the protesters at the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Officers injured dozens of victims in attacks that included nightsticks, tear gas and whips. The horrifying scene — dubbed Bloody Sunday — was filmed and televised across the nation, prompting outraged religious leaders and social activists to flock to Selma to participate in future protests.

Two days later, Martin Luther King Jr. joined the group, which had more than tripled to about 2,000 people, for a second attempt, but he turned the group around when the state troopers confronted them again on the bridge. On the third attempt, on March 21, 1965, King and approximately 2,000 supporters finally had what they needed to complete the march — a federal court order and the protection of U.S. Army troops and the Alabama National Guard.

The marchers arrived in Montgomery on March 25 and were greeted by close to 50,000 supporters — many of them white. Four days before the last march, President Lyndon Johnson introduced the voting rights legislation in Congress that was later voted into law as the Voting Rights Act of 1965. African Americans already had the right to vote — granted by the 15th amendment — but this act prohibited states from creating insurmountable barriers that prevented them from actually registering and voting.

Democratic National Convention – 1968

When the major political parties have their conventions to choose their parties’ presidential candidates, you expect some drama and turmoil and probably even some protests, but the reaction to the protests that occurred at the 1968 Democratic National Convention left the country stunned. The protests mostly focused on ending the Vietnam War and the continuing struggles of African Americans, a situation made worse by Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination earlier in the year.

The Democratic primaries leading up to the convention had already been plagued with drama and even tragedy when presidential hopeful Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in June. Before the convention, tension built throughout the city of Chicago with the arrival of several anti-war activist groups that applied for permits to stay in Lincoln Park and hold rallies at several key locations. Chicago was divided and in turmoil, and the convention delegates were guarded inside a virtual fortress at the convention venue.

Chicago Mayor Richard Daley ordered police to clear Lincoln Park of all protestors at the 11 p.m. park curfew the night before the convention started, and the conflict turned bloody when the officers attacked them with clubs and tear gas. The bitter fighting among the pro-war and anti-war delegates inside the convention the next day also raged out of control. Each subsequent day led to more protests and more police violence outside the convention. Inside, the delegate majority voted to support the war, leading to renewed chaos and fighting among the delegates as well.

A renewed standoff between the police and protestors outside the Hilton hotel again resulted in violence, with the police beating participants with clubs and their fists — but that time the violence was broadcast for a horrified America to watch. By the time the convention ended, the Democrats had alienated the American people and guaranteed the Republican candidate, Richard Nixon, would win the presidency.

This disastrous convention and the one that followed prompted the Democratic Party to review their nominating process and make critical changes. They tossed out the old protocols that allowed party leaders and other powerful people to choose the convention delegates — who then chose the nominee those powerful men wanted. Instead, they adopted the system they have today, where voters in caucuses and primaries determine the party’s nominee.