What Is The Bechdel Test And How Has It Changed Representation In Film?

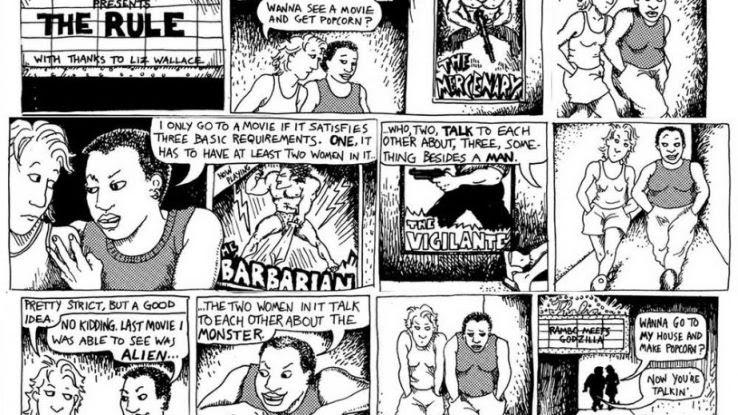

Representation and gender might be talked about rather commonly when discussing films, books, and other media of today. Back in 1985, the notion of a film actually being about women, as opposed to just featuring them, encouraged Alison Bechdel, a lesbian cartoonist, to create a witty aside about the issue.

The Bechdel Test is a great tool for measuring the quality and quantity of female characters in film, TV, books, and any other conceivable media. But this measure did not simply appear one day out of Bechdel’s head. Its origins are rooted in conversation, one that goes back farther than the test’s inception 35 years ago. The Bechdel Test addresses issues that have been prevalent throughout history.

What Is The Bechdel Test?

Nowadays, when content that millions or billions of people might see exists, a friend might ask if the popular story passes what’s called The Bechdel Test. Popularized by Alison Bechdel, passing The Bechdel Test simply means that the film adheres to three precepts:

1. Are there two or more named female characters?

2. Do they talk to each other?

3. Is their conversation about anything other than a man?

While women’s representation — or at least, discussion of women in media — might seem almost normalized in many conversations, this has not always been the norm, and still isn’t. According to GoogleTrends, not many people were really searching for The Bechdel Test until early 2008. That’s 13 years after the comic strip’s original release.

It’s okay to be unaware or unfamiliar with The Bechdel Test. Since the comic started off in a more alternative or underground setting, appearing in gay newspapers and anthologized by small presses, The Bechdel Test’s history is still developing.

A report found that only 33.1% of all speaking roles or named characters in the top 100 grossing films of that year were women or girls. So, despite the Bechdel Test’s 35 year old age — making it old enough to run for President — the movie measure is still relevant and perhaps necessary to analyze popular content. Women aren’t appearing as much in films and other popular media as men, and The Bechdel Test helps show us how.

Since the Bechdel Test has been “alive” for longer than it’s been brought up in casual conversation at the dinner table, it’s important to look into the Bechdel Test’s origins before they disappear, like an unpreserved film. It’s history is more complex than a teacher drumming up a pop quiz for their students, that’s for sure.

The History of Alison Bechdel: The Name Behind The Test

Alison Bechdel is the author of Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic and Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama . Born in 1960, she grew up in Pennsylvania before coming out at age 19 while attending Oberlin College. She cites Howard Cruse’s Gay Comix anthology as a major influence on her early work.

More recently, Bechdel received a MacArthur Genius grant in 2014. In 2015, a musical adaptation of Fun Home won five Tony Awards, including Best Musical.

Not long after graduating college, Bechdel penned the weekly comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For, which ran in gay newspapers from 1983 to 2008. The comic strip broke ground in terms of representation — there was not a lot of lesbian content, or even conrent about women, widely available at the time. Bechdel did not foresee the potential for one of those weekly comic strips to go viral decades later.

From 1929 to 1985 to Today

The Bechdel Test was established in 1985 in Alison Bechdel’s comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For. Alison Bechdel did not sit down one day at her sketchpad and say, “this will become the new standard of film, books, and TV. A rather low bar I might add!” The idea for the test, the author of the 28-year-long running comic strip has admitted, did not originally come from her.

Liz Wallace, a friend of Bechdel’s, told her about the test in conversation. Bechdel gave Wallace credit in her original comic strip and appreciates it when folks refer to the measure as The Bechdel-Wallace Test. Dykes to Watch Out For has a tone that is lighthearted, cheeky, and sometimes political and critical in a MAD Magazine or a The Onion type of way.

Bechdel gave Wallace credit in the comic strip’s very first panel. In “The Rule,” main character, Mo, takes a date to the movies. Underneath the title of that week’s strip reads, “with thanks to Liz Wallace.” Mo tells her date the three little rules that she started following, leaving the reader to wonder just how few movies Mo can actually watch. This is also why some folks alternatively refer to the Bechdel-Wallace Test as “Mo’s Movie Measure,” because it was Bechdel’s character that brought the test to life.

Bechdel has also mentioned that the idea at large came from queer icon Virginia Woolf and her book-length essay, A Room of One’s Own. Released in 1929, this foundational text discusses the landscape of fiction in Woolf’s time. In the essay, which draws on a lot of fiction and mixes genres much like Bechdel’s comics, Woolf laments the lack of female characters and women to write them. Woolf attributes the lack of educational opportunities for women as the source of this pain.

Historically, there weren’t as many content creators in Woolf’s time or earlier, so there was not a lot of content about women as a result. The Bechdel Test brings light to that issue.

Why We Need More Women in TV and Film

According to the United States Peace Corps, “women’s empowerment is a critical aspect of achieving gender equality. It includes increasing a woman’s sense of self-worth, her decision-making power, her access to opportunities and resources, her power and control over her own life inside and outside the home, and her ability to effect change.”

If women aren’t given their own stories, girls and women lack a blueprint for their potential and dreams. Including more female characters, ones with names and thoughts of their own, in stories on TV and in film is a great way to expose people to different walks of life. The Bechdel Test’s history may be rooted in the desire and hope for more of that energy.

Representation is not just something women are rallying behind. Calls for representation are growing when it comes to race, sexuality, disability, and other marginalized identities and groups. Different types of representation do not necessarily exclude people. Consuming media about different types of people, when that content is made well, oozes educational merit for all.

The Bechdel Test Is Part of a Conversation…Not the End of One

Alison Bechdel herself has said on multiple occasions that some of her favorite movies don’t pass the Bechdel Test and that is fine. Mo’s Movie Measure is not the be all/end all for women’s representation in content. The test has its flaws in that creators can treat the test like a hurdle that does not have to be relevant to the plot. Call Me By Your Name (2017), for example, “passes” the Bechdel Test by having two minor female characters, who happen to have names, discuss different types of pasta.

The Bechdel Test is, in essence, a break from films or books that feature all male casts and an acknowledgment of the frustration that can happen when there is only one woman on screen. It’s a test that’s made to fade into obscurity, but that hasn’t happened yet. However, failing the Bechdel Test does not mean that a film is not “about women.” For example, 2013’s Gravity, starring Sandra Bullock, does not pass the test but was still impactful enough to earn Bullock an Oscar nomination.

There’s even an archive of films dedicated to those that pass and fail The Bechdel-Wallace test. The archive is closing in at 9,000 films at this point in time. In 2020, the archive shows that 78 films passed the Bechdel Test out of 329 films released in the U.S. and Canada. In non-pandemic years, an average 600 or 700 films have been added to the archive annually since 2006. For example, the archive has almost 120 films passing for 2019 out of those couple hundred that were added. It can be neat to see this data unfold in real-time as films are released.

There are also other “Bechdel Tests” out there. The DuVernay Test, which is named after director Ava DuVernay, requires Black characters to have fully realized lives and not serve as props in white stories. For the Koeze-Dottle Test, a supporting cast must be more than 50% women to earn a passing score.

While Alison Bechdel will go down in history for her comics, graphic memoirs, and the Tony-award winning musical about her life, The Bechdel Test is an odd legacy to some degree. There may be a day when the test becomes irrelevant, but until then, we’re thankful to Alison Bechdel for bringing it to our attention.